ISSN: 1839-9940

J Genomics 2026; 14:1-9. doi:10.7150/jgen.125510 This volume Cite

Research Paper

De Novo Genome Assembly of the Myanmar Puddle Frog, Phrynoglossus myanhessei (Anura: Dicroglossidae)

1. Senckenberg Forschungsinstitut und Naturmuseum, 60325 Frankfurt a.M., Germany.

2. Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre (BiK-F), 60325 Frankfurt a.M., Germany.

3. LOEWE-Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics (TBG), Senckenberg Nature Research Society, 60325 Frankfurt a.M., Germany.

Received 2025-10-1; Accepted 2025-12-1; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

The Myanmar puddle frog, Phrynoglossus myanhessei, is a recently described, small dicroglossid frog distributed across central and southern Myanmar, typically inhabiting areas adjacent to small stagnant water bodies. With that new species description, rudimentary genome data from 30-fold Illumina sequencing were published as a novel approach in taxonomy to routinely publish genome data for new holotypes. While the data allowed to assemble the entire mitochondrial genome, it was not possible to extract basic population genetic data. Therefore, we present a de novo PacBio CLR genome assembly of P. myanhessei, to aid population genomic, evolutionary and taxonomic studies. The assembled genome has a size of 2.28 Gbp, with a scaffold N50 of 44 kbp and largest scaffold being 270 kbp long. BUSCO analysis indicates a completeness score of 49%, with 26.9% complete and 22.3% fragmented BUSCOs. Approximately 43% of the genome consists of repetitive elements and about 22,500 genes could be predicted. While not an optimal assembly, the new P. myanhessei genome is a valuable resource for follow-up studies and for closing the gap in amphibian genome representation.

Keywords: whole genome assembly, Phrynoglossus myanhessei, Dicroglossidae, Myanmar, holotype sequencing

Introduction

In addition to classical taxonomy, biodiversity is increasingly studied and described by Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) data analyses. However, genomic representation of species remains uneven even among vertebrates with most genome sequences derived from mammals (~4460 genomes) and birds (~2300 genomes) (National Center for Biotechnology Information; last accessed 21st July 2025; (1-3)). Amphibians are a rich tetrapod class with about 8900 species (4), representing a vertebrate class that includes the most threatened species, with nearly half of them being IUCN listed (5,6). As an ancient tetrapod lineage, they are globally distributed (except in the Arctic and Antarctica) and exhibit a unique diversity of traits, lifestyles, behaviours and reproductive strategies (7-12). Because of their rapid growth rate and high abundance, they serve as key components of food webs (13,14). These features make them attractive subjects for various scientific fields, including developmental biology, medical research, ecology and evolution (2,3). Despite their role of model organisms, they are still underrepresented in genomic studies utilizing NGS approaches (2,3).

To date, many studies on phylogenetic and taxonomic relationships of amphibians rely on a limited number of mitochondrial and nuclear markers (15-18). Recent genome sequencing initiatives, like the Earth Bio Genome project (19), produce and analyse large-scale genomic datasets. These allow for the investigation of genetic structures at increasingly broader geographical scales and higher resolution, even in non-model organisms such as amphibians (20,21), but have not reached momentum in this field. In addition, the assembly of amphibian genomes can often be challenging due to their large size and high repeat content (3,12,22), which are part of the reason for their underrepresentation among published genomes (1,2,23). Further limiting factors are the high costs and computational resources needed for analysing and assembling such genomes (24) as well as access to high-quality tissue for genome sequencing.

Compared to 4,400 mammalian genomes available on NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information; last accessed 3rd July 2025) covering two-thirds of all known mammal species, over the past decade, only about 180 anuran genomes have been published. The majority of these are represented by the families Hylidae (16 genomes), Bufonidae (12 genomes) and Ranidae (10 genomes). This stark discrepancy highlights the need for high-quality genome assemblies particularly from underrepresented amphibian lineages.

The family Dicroglossidae, fork-tongued frogs, comprises a large group of frogs distributed from Sub-Saharan Africa through India to Southeast Asia, forming a significant component of local amphibian communities. It includes over 245 species (4), but genome assemblies are currently only available for four of them, three belonging to the subfamily Dicroglossinae (Hoplobatrachus occipitalis, Nanorana parkeri and Quasipaa spinosa) and one to the subfamily Occidozyginae. Within the latter, only one rough draft genome based on 30-fold Illumina sequences is available for Phrynoglossus myanhessei (Figure 1). This species has been recently described from Myanmar (25) belonging to the genus Phrynoglossus (Peters 1867). Members of this genus are characterized by a fleshy and swollen tongue, the absence of vomerine teeth, slightly swollen digit tips, a distinct tympanum, skin covered by extensive mucous (“slimy touch”), a grey throat and both an axillar and inguinal amplexus (25,26). They are semiaquatic animals that tend to sit at the edge of small and shallow temporary water bodies (4,25). P. myanhessei remains poorly understood in terms of its natural history and ecology. Its known distribution is currently restricted to the central and southern regions of Myanmar, with no records from the Malay Peninsula (4).

The available genomic data of P. myanhessei were published in 2021 as a genome resource (1.8 Gbp) with high fragmentation (N50 1.5 kbp) and low completeness (BUSCO: 8.5%). They were released alongside its taxonomic description to provide basic genomic information for a newly described holotype and to support future research (25). As proof of principle to promote type-specimen genomics (27), the mitochondrial genome and a few nuclear genes could be identified in the original publication. The 30-fold Illumina paired-end coverage was an economic way to document its entire genome as a routine dataset for new species descriptions of new holotypes. However, its deeper information could only be extracted by mapping to a reference genome.

To improve the genome quality of this holotype, we generated Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) long-reads and applied Illumina short-read error correction, resulting in an improved reference genome for this genus.

Male holotype of Phrynoglossus myanhessei (SMF 103841) in life. Specimen stored in the collection at Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt, Germany. Photo by GK published in Köhler et al. (2021).

Materials and Methods

Taxon sampling

The sequenced male specimen of Phrynoglossus myanhessei (field number GK 6728; museum voucher SMF 103841) was collected by Gunther Köhler (GK) on 6 July 2017 at East Yangon University, Yangon Province, Myanmar (16.77737N, 96.24065E, WGS 1984). The specimen is stored at the herpetological collection at the Senckenberg Museum, Frankfurt (SMF), Germany.

Genomic library preparation

The protocols for DNA extraction and preparation for Illumina short-read sequencing are described in detail in Köhler et al. (2021) [25]. The short reads were deposited by Köhler et al. (2021) [25] under the accession number SRR13288470.

For PacBio consensus long read (CLR) sequencing genomic DNA was extracted from 2.5 mg tongue tissue following the standard phenol chloroform protocol (28). The obtained DNA was resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris Cl, 0.1 mM EDTA) and stored at -20 °C. Quality of the extracted DNA was assessed using TapeStation 2200 from Agilent Technologies (29).

Genome assembly and scaffolding

Based on the raw sequencing data, a k-mer profile was generated using Jellyfish 2.3.0 (30) and visualized with GenomeScope 2.0 (31,32). The quality of the raw reads was assessed using FastQC 0.11.9 (33). Adapter sequences and low-quality bases were removed using Trimmomatic 0.39 (34).

The obtained long reads of SMF 103841 were assembled using Flye 2.9.2 with the pacbio-raw flag and an estimated genome size of 2.5 g (35). The assembly was polished with long reads using Racon 1.5 (36) and deduplicated short reads using Pilon 1.24 (37). To clean the short reads before polishing, they were mapped against the assembly using BWA 0.7.17 (38) and Samtools 1.17 (39). Additionally, duplicates were marked using Picard 3.0 (40). To increase continuity, long-read scaffolding was performed with LongStitch 1.0.5 (41). To improve the correctness of the scaffolded assembly, gap closing was conducted with TGS-GapCloser 1.2.1 (42).

Assembly quality assessment

Contiguity and basic statistical data of the obtained assembly were assessed using QUAST 5.2.0 (43). To check the assembly for contamination by other organisms, the contigs were aligned with the NCBI database using blastn algorithm (44). The results were visualized with Blobtools 1.1.1 using the “bestsum” algorithm (45). Contigs assigned to lineages other than vertebrates were checked for vertebrate BUSCOs using BUSCO 5.4.3 with the tetrapoda orthologous gene set (tetrapoda_odb10) (46). Contigs were maintained for the assembly when vertebrate BUSCOs were detected. To improve the correctness of the obtained assembly, contigs smaller than 500bp were removed. In addition, contigs were aligned with the NCBI database using blastn algorithm to remove contigs assigned to the mitochondrial genome (44). Furthermore, BUSCO 5.4.3 was used to evaluate the completeness of the assembled genome using the vertebrate orthologous gene set (vertebrata_odb10) (46).

Genome annotation

Repeat annotation: Repeat annotation was performed using RepeatModeler 2.0.4 and RepeatMasker 4.1.5 (47,48). First, a species-specific repeat library was generated with RepeatModeler 2.0.4 (using NCBI rmblast 2.14.0+ engine) including RECON 1.08 (49), RepeatScout 1.0.6 (50), LTRharvest (51) and LTR_retriever (52). This library was then combined with lineage-specific repeats from Dfam (53) using famdb.py to create a custom library. Repeat masking was performed with RepeatMasker using the combined library, applying both hard and soft masking. Finally, the repeat landscape was plotted based on Kimura 2-parameter divergence using RepeatMasker utilities.

Gene annotation: Protein-coding gene models were predicted using GeMoMa 1.9 (54), which transfers gene annotations from multiple reference species to the target assembly via homology-based projection and intron position conservation. The genome was annotated with the GeMoMa pipeline, using annotations and genomes from seven amphibian references (Bufo bufo GCF_905171765.1, Bufo gargarizans GCF_014858855.1, Hyla sarda GCF_029499605.1, Nanorana parkeri GCF_000935625.1, Rana temporaria GCF_905171775.1, Xenopus laevis GCF_017654675.1 and Xenopus tropicalis GCF_000004195.4). GeMoMa was run with realignment enabled (GeMoMa.Score=ReAlign) to output predicted coding sequences and proteins. Statistics of the predicted proteins were summarized using AGAT (55). The final protein set was assessed for completeness using BUSCO 5.4.3 in “protein” mode with the vertebrate ortholog set (vertebrata_odb10) (46).

Variant calling and demographic inference

Short reads were mapped to the final assembly using BWA-MEM 0.7.17 (38) and duplicate reads were removed using “MarkDuplicates” from Picard 3.0.0-1 (40). Mapping quality was assessed with Qualimap 2.2.1 (56).

Samtools 1.19 was used to calculate site depth statistics (57). Variant calling was done using bcftools 1.19 “mpileup” and “call -m” (39). Variants were filtered based on read depth (DP) using bcftools filter, retaining only those with DP between 30 and 75 to exclude low-confidence and highly covered sites. Genome-wide variant statistics were obtained using bcftools “stats”. Genome-wide heterozygosity (HE) was calculated from variant statistics as the proportion of heterozygous genotypes relative to total genotypes. The genome-wide genotype error rate was estimated as the proportion of non-reference homozygous calls relative to the total number of genotype sites obtained from the variant statistics to assess sequencing accuracy. We estimated effective population size (Ne) based on HE and mutation rate (μ) using the formula:

Ne=HE / (4×μ)

We based our mutation rate on synonymous substitution rates reported by Session et al. (2016) [58] for Xenopus laevis, who estimated an absolute substitution rate of approximately 3.0 × 10⁻⁹ substitutions per site per year, excluding CpG sites. Assuming a generation time of 2 years for X. laevis, this translates to a per-generation mutation rate of approximately 6.0 × 10⁻⁹ (0.6 × 10⁻⁸) substitutions per site per generation. However, because direct estimates for our study species are unavailable, and to account for variation in mutation rates among amphibians and vertebrates more broadly, we also considered a plausible range of 0.5-1.0 × 10⁻⁸ mutations per site per generation (59,60).

Data availability

The genome assembly generated during this project is accessible on GenBank (Bioproject PRJNA687006; Accession No. JBRATO000000000). Supplemental material available at Journal of Genomics online.

Results

Genome sequencing and assembly

High quality genomic DNA with an average length of >10kbp could be extracted from tongue tissue (see Supplementary Figure 1). Since the sample has been stored in Ethanol for ~5 years, it was not suitable for RNA isolation and generation of a transcriptome.

PacBio CLR sequencing produced 119 Gb of long read data with a mean read length of 8,047 bp, a total of 7,910,035 reads and a total length of 63,653,327,111 bp. Illumina short-read sequences yielded two identical files of 211 Gb short-read data, each containing 308,075,534 reads with a total length of 46,211,330 bp (Table 1).

Summary statistics of the raw (1) and the filtered and trimmed (2) Illumina short read data of Phrynoglossus myanhessei SMF 103841.

| (1) Statistics of raw short reads | ||

| No. of short reads | 308,075,534 | |

| Average read length [bp] | 150 | |

| Total length [bp] | 46,211,330,100 | |

| Duplicates [%] | 25.3 | |

| GC [%] | 42 | |

| (2) Statistics of trimmed short reads | ||

| forward | reversed | |

| No. of short reads | 301,535,351 | 301,535,351 |

| Average read length [bp] | 150 | 150 |

| Total length [bp] | 45,227,130,304 | 45,226,425,599 |

| Duplicates [%] | 24.9 | 24.3 |

| GC [%] | 42 | 42 |

The de novo assembly of Phrynoglossus myanhessei from PacBio and Illumina data resulted in a genome of 2.28 Gbp consisting of 70,197 scaffolds, with a scaffold of N50 of 44 Kbp and L50 of 16,441 bp (Table 2). Estimated long-read and short-read coverage of the assembly were 14.6× and 13.3×, respectively.

Summary statistics of the Phrynoglossus myanhessei SMF 103841 scaffold-level reference genome. Details on assembly statistics (1) and BUSCO analysis (2) are shown.

| (1) Statistics of long reads | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| contigs | scaffolds | ||

| Total no. | 77,560 | 70,197 | |

| Total length [bp] | 2,407,983,688 | 2,279,771,963 | |

| Largest contig [bp] | 289,698 | 271,019 | |

| N50 | 42,693 | 44,633 | |

| L50 | 18,255 | 16,441 | |

| GC [%] | 42.72 | 42.7 | |

| Ns per 100 kbp | 0 | 185.5 | |

| No. of total Ns | 0 | 4,229,927 | |

| Mean long read coverage [x] | 14.6 | ||

| Mapped long reads [%] | 92.1 | ||

| Mean short read coverage [x] | 13.3 | ||

| Mapped short reads [%] | 85.6 | ||

| (2) BUSCO completeness (n = 3354) | |||

| S: 26.6% | D: 0.3% | F: 22.3% | M: 50.8% |

Blobtools classified 73% of scaffolds as Chordata, ~1% as arthropoda and 7% unknown (see Supplementary Figure 2). BUSCO analysis of the cleaned assembly recovered a total of 49.2% BUSCOs, including 26.9% complete (Table 2).

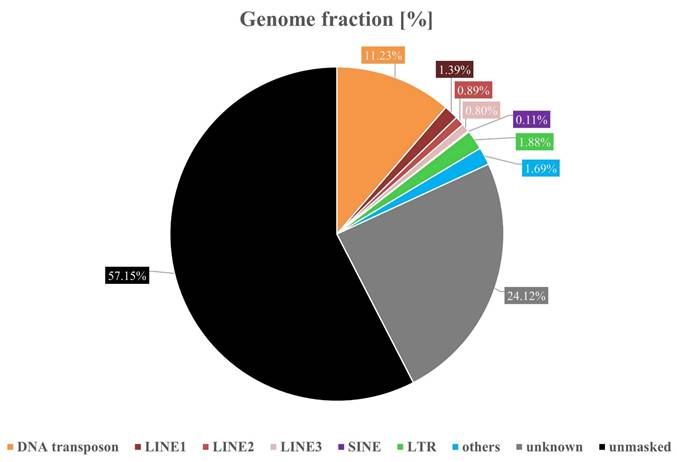

Genome fraction of the Phrynoglossus myanhessei (SMF 103841) de novo assembly showing the proportion of repetitive elements (with the black area representing the non-repetitive portion of the genome).

Genome annotation

Repeat masking identified 42.9% of the de novo genome as repetitive elements (RE) (Figure 2). Of these, 5.23% were classified as retroelements, including 0.08% SINEs, 3.08% LINEs (1.39% LINE1, 0.89% LINE2 and 0.8% LINE3), and 1.88% LTR elements. DNA transposons accounted for 11.23%, rolling-circle elements for 0.05%, small RNAs for 0.03%, satellites for 0.13% and simple repeats for 1.53%. Notably, 24.12% of the repetitive sequences could not be assigned to known classes.

Genome annotation, combining de novo and homology-based repeat identification, resulted in 22,508 genes, 29,402 mRNAs, and 175,281 coding sequences (CDSs). The annotated genes had an average length of 9,168 bp. Each CDS is composed of an average of 5.5 exons and 4.5 introns with mean exon and intron lengths of 210 bp and 1777 bp. BUSCO analysis of the predicted proteins identified 31.0% complete proteins, of which 8.2% were duplicated. Additionally, 16.4% of the predicted proteins were fragmented and 52.6% were missing (total n=3352).

Variant calling and demographic inference

Variant Calling recovered about 74.6 million sites, of which 74.3 million were monomorphic and about 268,000 were biallelic variants. Genome-wide heterozygosity (Ho) was estimated at 0.358%. Genotype calls were highly accurate, with a low estimated genotype error rate of about 0.0019%.

Assuming mutation rates ranging from 0.5 × 10⁻⁸ to 1.0 × 10⁻⁸ per site per generation, effective population size (Ne) was estimated to range from approximately 90,000 to 180,000 individuals, indicating substantial genetic diversity in the studied population.

Discussion

For more than 250 years, species descriptions in taxonomy have relied on physical specimens—specifically the holotype—which is collected, examined, described in published literature, and permanently deposited in natural history museum collections (27). Taxonomic comparisons, subspecies delimitations and assessments of closely related taxa require access to these name-bearing specimens, the holotype (27,61,62). This often necessitates either complicated loans of the specimen or travel to holding institution. However, over time, type specimens inevitably deteriorate: colors fade, anatomical features shrink, and fur or feathers may be lost (27).

Genomic data provide a permanent and globally accessible complement to traditional type material. Generating 20-30x short-read coverage of a genome providing comprehensive data that is inexpensive in comparison to the logistics of field collection and long-term specimen curation. However, genomic data requires decoding through mapping to a reference genome of a closely related species, which is often unavailable for non-model organisms, such as in our case Phrynoglossus myanhessei.

For more in-depth taxonomic, population genomic, or evolutionary studies, a draft reference genome becomes essential. Such a genome enables the retrieval of protein-coding genes, estimation of heterozygosity, and reconstruction of demographic history (27). Additionally, the reference genome can serve as a scaffold to map short reads from closely related individuals, facilitating accurate species delimitation—one of the fundamental goals of taxonomy.

Here, we present an improved genome assembly of Phrynoglossus myanhessei. However, the assembly remains non-contiguous, as measured by scaffold N50 and L50 metrics. High heterozygosity complicates genome assembly, even with long-read platforms such as PacBio, due to the increased presence of alternative haplotypes. This often leads to fragmented assemblies with reduced contiguity, reflected in lower N50 values (63,64).

Additional factors might likely contribute to the limited contiguity and completeness of the assembly, including only moderate DNA integrity (despite >15 kb fragments), the reliance on PacBio CLR and short-read Illumina data, and the absence of RNA-seq or linked-read data. While high quality DNA with a length of >15kpb could be extracted from the material suitable for PacBio CLR sequencing, the material did not allow for additional RNA sequencing due to its nearly five years of ethanol preservation and frozen storage. The sequencing strategy of using PacBio CLR in combination with Illumina short-reads and the resulting read data are limiting read length and quality compared to high-quality assemblies that mainly rely on including transcriptome or linked-read technologies. The short-read Illumina data although having high read quality are insufficient in resolving repetitive regions and structural complexity and lead to fragmentation and gaps in the assembly (65).

The relatively low BUSCO values (~50%) likely underestimates the true completeness of this novel genome assembly. BUSCO analysis was conducted using a general vertebrate database rather than one tailored to amphibians or anurans (66,67). This bias can lead to underestimating predicted gene or protein completeness. However, when compared with other amphibian genome assemblies generated using similar sequencing and analysis approaches, our results are consistent, typically showing ~20% lower completeness than highly scaffolded or chromosome-level assemblies (68-71).

This reference bias also extends to repeat annotations: when homology-based repeat libraries are incomplete, true genes may be misclassified as repetitive elements, artificially increasing the proportion of “unknown” repeats (3,72). In our genome assembly, the total repeat content is slightly lower than that reported for other dicroglossid anurans (47-64%) yet remains well within the known range documented for anurans (23-82%) (12). In contrast, the initial draft assembly of P. myanhessei (GCA_022657655.1) showed a higher repeat content (47.65%), likely a consequence of the greater fragmentation of the assembly, which can lead to an overestimation of repetitive samples.

Moreover, our study reveals that P. myanhessei exhibits relatively high heterozygosity and effective population size compared to other amphibians. Threatened species in particular often exhibit reduced heterozygosity, due to often small and fragmented populations and limited connectivity among them (73,74). Likewise, formerly widespread amphibians such as the boreal toad (Anaxyrus boreas) now display markedly lower heterozygosity and nucleotide diversity, likely reflecting historical bottleneck effects and recent population declines (75-77). In contrast, heterozygosity in P. myanhessei (~0.35%) is comparable to that of the African clawed frog (Xenopus tropicalis) (~0.3%), a widely distributed species without signs of demographic decline (78).

The relatively high heterozygosity in P. myanhessei suggests a large and stable population. Field observations support this interpretation: the species is common across its distribution range, readily occupying both natural and anthropogenic habitats, and breeds opportunistically, with males calling from any suitable puddle (GK pers. comm.). Such ecological traits facilitate gene flow within a population and thus help maintain genetic diversity by mitigating the impacts of genetic drift and inbreeding (79-81).

The genome annotation performed with GeMoMa predicted approximately 22,000 protein-coding genes, which lies within the expected range for vertebrate genomes (82). Despite the fragmented nature of the assembly, this relatively high gene count underscores the value of homology-based gene prediction tools, which can recover conserved gene models by aligning the fragmented scaffolds to a reference genome of a related species (83). However, the high fragmentation still limits annotation accuracy and completeness, contributing to the relatively low BUSCO completeness score (~30%). This likely reflects methodological constraints, such as fragmentation of gene models, partial or misassembled exons, and limitations of the available reference databases, rather than true biological absence. Consequently, many functional genes are likely present in the genome but were not detected or fully annotated by BUSCO.

Despite these limitations, the assembly remains suitable as a reference for mapping-based analyses, including population genomics and variant calling. Assemblies of comparable quality have been successfully used in other anuran population genomic studies, such as the Phyllomedusa burmeisteri species group (71). The recovered protein-coding genes therefore remain valuable for exploring controversial phylogenetic relationships within the subfamily Occidozyginae.

Abbreviations

BUSCO: Benchmarking Universal Single Copy Orthologs; CDS: coding sequences; CLR: consensus long read (sequencing); GeMoMa: Gene Model Mapper; GK: Gunther Köhler; HE: heterozygosity; LINE: long interspersed nuclear elements; LTR: long terminal repeats; Ne: effective population size; NGS: Next Generation Sequencing; RE: repetitive elements; SINE: short interspersed nuclear elements; SMF: Senckenberg Museum Frankfurt.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Prof. Dr. Ni Lar Than for her help during field work and for issuing collecting permits. We are grateful to Dr. Nyi Nyi Kyaw, Director General, Forest Department, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, Myanmar, for issuing the collecting permits, U Hla Maung Thein, Director General, Environmental Conservation Department, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, Myanmar, for issuing the permission to access the genetic resources as in compliance with the Nagoya Protocol, and to Dr. Naing Zaw Htun, Director, Nature and Wildlife Conservation Division, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, Myanmar, for issuing the exportation permits. We are especially grateful to Dr. Kyaw Kyaw Khaung, Rector, East Yangon University, Thanlyin, for supporting us to obtain all necessary permissions from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, Myanmar.

We are grateful for the TBG-lab-Team (Carola Greve, Alexander Ben Hamadou, Charlotte Gerheim) for help with the sample preparation and submission to the sequencing provider. The present study is a product of the Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics (LOEWE-TBG) as part of the “LOEWE - Landes-Offensive zur Entwicklung Wissenschaftlich-ökonomischer Exzellenz” program of Hesse's Ministry of Higher Education, Research, and the Arts as well as the Leibniz Association.

We thank Dr. Maya Beukes, Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg Frankfurt, whose helpful review of the writing style greatly improved the manuscript.

Author ORCIDs

Katharina Geiß: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3180-352X; Gunther Köhler: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2563-5331; Axel Janke: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9394-1904.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Hotaling S, Kelley JL, Frandsen PB. Toward a genome sequence for every animal: Where are we now? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021;118(52):e2109019118

2. Womack MC, Steigerwald E, Blackburn DC, Cannatella DC, Catenazzi A, Che J. et al. State of the Amphibia 2020: A Review of Five Years of Amphibian Research and Existing Resources. Ichthyology & Herpetology. 2022;110(4):638-61

3. Kosch TA, Torres-Sánchez M, Liedtke HC, Summers K, Yun MH, Crawford AJ. et al. The Amphibian Genomics Consortium: advancing genomic and genetic resources for amphibian research and conservation. BMC Genomics. 2024;25:1025

4. Frost DR. American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA. 2024. Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.2. https://amphibiansoftheworld.amnh.org/index.php.

5. Scheele BC, Pasmans F, Skerratt LF, Berger L, Martel A, Beukema W. et al. Amphibian fungal panzootic causes catastrophic and ongoing loss of biodiversity. Science. 2019;363(6434):1459-63

6. IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatend Species. Version 2022-2. https://www.iucnredlist.org. 2022

7. Brown JL, Morales V, Summers K. A Key Ecological Trait Drove the Evolution of Biparental Care and Monogamy in an Amphibian. Am Nat. 2010;175(4):436-46

8. Nunes-de-Almeida CH, Haddad CFB, Toledo LF. A revised classification of the amphibian reproductive modes. Salamandra. 2021;57(3):413-27

9. Schulte LM, Ringler E, Rojas B, Stynoski JL. Developments in Amphibian Parental Care Research: History, Present Advances, and Future Perspectives. Herpetological Monographs. 2020;34(1):71

10. Liu Y, Shi D, Wang J, Chen X, Zhou M, Xi X. et al. A Novel Amphibian Antimicrobial Peptide, Phylloseptin-PV1, Exhibits Effective Anti-staphylococcal Activity Without Inducing Either Hepatic or Renal Toxicity in Mice. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:565158

11. De Angelis M, Casciaro B, Genovese A, Brancaccio D, Marcocci ME, Novellino E. et al. Temporin G, an amphibian antimicrobial peptide against influenza and parainfluenza respiratory viruses: Insights into biological activity and mechanism of action. The FASEB Journal. 2021;35(2):e21358

12. Kosch TA, Crawford AJ, Lockridge Mueller R, Wollenberg Valero KC, Power ML, Rodríguez A. et al. Comparative analysis of amphibian genomes: An emerging resource for basic and applied research. Mol Ecol Resour. 2025;25(1):e14025

13. Colón-Gaud C, Whiles MR, Kilham SS, Lips KR, Pringle CM, Connelly S. et al. Assessing ecological responses to catastrophic amphibian declines: Patterns of macroinvertebrate production and food web structure in upland Panamanian streams. Limnol Oceanogr. 2009;54(1):331-43

14. Zipkin EF, DiRenzo GV, Ray JM, Rossman S, Lips KR. Tropical snake diversity collapses after widespread amphibian loss. Science. 2020;367(6479):814-6

15. Bossuyt F, Brown RM, Hillis DM, Cannatella DC, Milinkovitch MC. Phylogeny and biogeography of a cosmopolitan frog radiation: Late cretaceous diversification resulted in continent-scale endemism in the family ranidae. Syst Biol. 2006;55(4):579-94

16. Chen WC, Peng WX, Liu YJ, Huang Z, Liao XW, Mo YM. A new species of Occidozyga Kuhl and van Hasselt, 1822 (Anura: Dicroglossidae) from Southern Guangxi, China. Zool Res. 2022;43(1):85-9

17. Flury JM, Haas A, Brown RM, Das I, Pui YM, Boon-Hee K. et al. Unexpectedly high levels of lineage diversity in Sundaland puddle frogs (Dicroglossidae: Occidozyga Kuhl and van Hasselt, 1822). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2021;163:107210

18. Hofmann S, Baniya CB, Litvinchuk SN, Miehe G, Li J, Schmidt J. Phylogeny of spiny frogs Nanorana (Anura: Dicroglossidae) supports a Tibetan origin of a Himalayan species group. Ecol Evol. 2019;9(24):14498-511

19. Lewin HA, Richards S, Lieberman Aiden E, Allende ML, Archibald JM, Bálint M. et al. The Earth BioGenome Project 2020: Starting the clock. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022;119(4):e2115635118

20. Chan KO, Hutter CR, Wood PL, Grismer LL, Das I, Brown RM. Gene flow creates a mirage of cryptic species in a Southeast Asian spotted stream frog complex. Mol Ecol. 2020;29(20):3970-87

21. Goodwin S, McPherson JD, McCombie WR. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(6):333-51

22. Zuo B, Nneji LM, Sun YB. Comparative genomics reveals insights into anuran genome size evolution. BMC Genomics. 2023;24(1):379

23. Sun YB, Xiong ZJ, Xiang XY, Liu SP, Zhou WW, Tu XL. et al. Whole-genome sequence of the Tibetan frog Nanorana parkeri and the comparative evolution of tetrapod genomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015;112(11):E1257-E1262

24. Sun YB, Zhang Y, Wang K. Perspectives on studying molecular adaptations of amphibians in the genomic era. Zool Res. 2020;41(4):351-64

25. Köhler G, Vargas J, Than NL, Schell T, Janke A, Pauls SU. et al. A taxonomic revision of the genus Phrynoglossus in Indochina with the description of a new species and comments on the classification within Occidozyginae (Amphibia, Anura, Dicroglossidae). Vertebr Zool. 2021;71:1-26

26. Trageser S, Al-Razi H, Maria M, Nobel F, Asaduzzaman M, Rahman SC. A new species of Phrynoglossus Peters, 1867; Dicroglossidae) from southeastern Bangladesh, with comments on the genera Occidozyga and Phrynoglossus. PeerJ. 2021;9:1-32

27. Letsch H, Greve C, Hundsdoerfer AK, Irisarri I, Moore JM, Espeland M. et al. Type genomics: a Framework for integrating Genomic Data into Biodiversity and Taxonomic research. Syst Biol. 2025 syaf040

28. Sambrook J, Russell WD. Protocol 1: DNA isolation from mammalian tissue. In: Sambrook J, Russell WD, editors. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. 2001 p. 623-7

29. Padmanaban A, Inche A, Gassmann M, Salowsky R. High-Throughput DNA Sample QC Using the Agilent 2200 Tapestation System. Journal of Biomolecular Techniques. 2013;24(Suppl):41

30. Marçais G, Kingsford C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k -mers. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(6):764-70

31. Ranallo-Benavidez TR, Jaron KS, Schatz MC. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1432

32. Vurture GW, Sedlazeck FJ, Nattestad M, Underwood CJ, Fang H, Gurtowski J. et al. GenomeScope: fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(14):2202-4

33. Andrews S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. 2010 [cited. 2022 Nov 2]. Available from: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/

34. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114-20

35. Kolmogorov M, Yuan J, Lin Y, Pevzner PA. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(5):540-6

36. Vaser R, Sović I, Nagarajan N, Šikić M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 2017;27(5):737-46

37. Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, Sakthikumar S. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112963

38. Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv:13033997v2 [q-bioGN]. 2013

39. Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, Marshall J, Ohan V, Pollard MO. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience. 2021;10(2):giab008

40. Picard toolkit. Broad Institute, GitHub repository. Broad Institute. 2018

41. Coombe L, Li JX, Lo T, Wong J, Nikolic V, Warren RL. et al. LongStitch: high-quality genome assembly correction and scaffolding using long reads. BMC Bioinformatics. 2021;22(1):534

42. Xu M, Guo L, Gu S, Wang O, Zhang R, Peters BA. et al. TGS-GapCloser: A fast and accurate gap closer for large genomes with low coverage of error-prone long reads. Gigascience. 2020;9(9):giaa094

43. Mikheenko A, Prjibelski A, Saveliev V, Antipov D, Gurevich A. Versatile genome assembly evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(13):i142-50

44. Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Wagner L, Miller W. A Greedy Algorithm for Aligning DNA Sequences. Journal of Computational Biology. 2000;7(1-2):203-14

45. Laetsch DR, Blaxter ML. BlobTools: Interrogation of genome assemblies. F1000Res. 2017;6:1287

46. Manni M, Berkeley MR, Seppey M, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: Assessing Genomic Data Quality and Beyond. Curr Protoc. 2021;1(12):e323

47. Flynn JM, Hubley R, Goubert C, Rosen J, Clark AG, Feschotte C. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020;117(17):9451-7

48. Smit A, Hubley R, Green P. RepeatMasker Open-4.0. http://www.repeatmasker.org.; 2013

49. Bao Z, Eddy SR. Automated De Novo Identification of Repeat Sequence Families in Sequenced Genomes. Genome Res. 2002;12(8):1269-76

50. Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(Suppl 1):i351-8

51. Ellinghaus D, Kurtz S, Willhoeft U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9(1):18

52. Ou S, Jiang N. LTR_retriever: A Highly Accurate and Sensitive Program for Identification of Long Terminal Repeat Retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 2018;176(2):1410-22

53. Storer J, Hubley R, Rosen J, Wheeler TJ, Smit AF. The Dfam community resource of transposable element families, sequence models, and genome annotations. Mob DNA. 2021;12(1):2

54. Keilwagen J, Hartung F, Grau J. GeMoMa: Homology-Based Gene Prediction Utilizing Intron Position Conservation and RNA-seq Data. 2019. 161-77.

55. Dainat J. Another Gtf/Gff Analysis Toolkit (AGAT): Resolve interoperability issues and accomplish more with your annotations. Plant and Animal Genome XXIX Conference: https://github.com/NBISweden/AGAT. 2022

56. Okonechnikov K, Conesa A, García-Alcalde F. Qualimap 2: advanced multi-sample quality control for high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32(2):292-4

57. Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078-9

58. Session AM, Uno Y, Kwon T, Chapman JA, Toyoda A, Takahashi S. et al. Genome evolution in the allotetraploid frog Xenopus laevis. Nature. 2016;538(7625):336-43

59. Roach JC, Glusman G, Smit AFA, Huff CD, Hubley R, Shannon PT. et al. Analysis of Genetic Inheritance in a Family Quartet by Whole-Genome Sequencing. Science. 2010;328(5978):636-9

60. Crawford AJ. Relative Rates of Nucleotide Substitution in Frogs. J Mol Evol. 2003;57(6):636-41

61. Haber MH. How to misidentify a type specimen. Biol Philos. 2012;27(6):767-84

62. Sluys R. Attaching Names to Biological Species: The Use and Value of Type Specimens in Systematic Zoology and Natural History Collections. Biol Theory. 2021;16(1):49-61

63. Guiglielmoni N, Houtain A, Derzelle A, Van Doninck K, Flot JF. Overcoming uncollapsed haplotypes in long-read assemblies of non-model organisms. BMC Bioinformatics. 2021;22(1):303

64. Kajitani R, Toshimoto K, Noguchi H, Toyoda A, Ogura Y, Okuno M. et al. Efficient de novo assembly of highly heterozygous genomes from whole-genome shotgun short reads. Genome Res. 2014;24(8):1384-95

65. Treangen TJ, Salzberg SL. Repetitive DNA and next-generation sequencing: computational challenges and solutions. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(1):36-46

66. Bachler A, Walsh TK, Rane RV, Pandey G. Chimeric mis-annotations of genes remain pervasive in eukaryotic non-model organisms. BMC Genomics. 2025;26(1):630

67. Malde K, Jonassen I. Repeats and EST analysis for new organisms. BMC Genomics. 2008;9(1):23

68. Streicher JW, Wellcome Sanger Institute Tree of Life Programme Darwin Tree of Life Consortium. The genome sequence of the common toad, Bufo bufo (Linnaeus, 1758). Wellcome Open Res. 2021;6(281):1-12

69. Li Q, Guo Q, Zhou Y, Tan H, Bertozzi T, Zhu Y. et al. A draft genome assembly of the eastern banjo frog Limnodynastes dumerilii dumerilii (Anura: Limnodynastidae). GigaByte. 2020;2020:1-13

70. Wu W, Gao YD, Jiang DC, Lei J, Ren JL, Liao WB. et al. Genomic adaptations for arboreal locomotion in Asian flying treefrogs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022;119(13):e2116342119

71. Andrade P, Lyra ML, Zina J, Bastos DFO, Brunetti AE, Baêta D. et al. Draft genome and multi-tissue transcriptome assemblies of the Neotropical leaf-frog Phyllomedusa bahiana. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics. 2022;12(12):jkac270

72. Ou S, Su W, Liao Y, Chougule K, Agda JRA, Hellinga AJ. et al. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):275

73. Frankham R. Relationship of Genetic Variation to Population Size in Wildlife. Conservation Biology. 1996;10(6):1500-8

74. Spielman D, Brook BW, Frankham R. Most species are not driven to extinction before genetic factors impact them. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101(42):15261-4

75. Murphy MA, Evans JS, Storfer A. Quantifying Bufo boreas connectivity in Yellowstone National Park with landscape genetics. Ecology. 2010;91(1):252-61

76. Trumbo DR, Hardy BM, Crockett HJ, Muths E, Forester BR, Cheek RG. et al. Conservation genomics of an endangered montane amphibian reveals low population structure, low genomic diversity and selection pressure from disease. Mol Ecol. 2023;32(24):6777-95

77. Lucid MK, Ehlers S, Robinson L, Sullivan J. Genetic structure not detected in northern Idaho and Northeast Washington Western toad (Anaxyrus boreas) populations. Northwestern Naturalist. 2021;102(1):89-93

78. Showell C, Carruthers S, Hall A, Pardo-Manuel de Villena F, Stemple D, Conlon FL. A Comparative Survey of the Frequency and Distribution of Polymorphism in the Genome of Xenopus tropicalis. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e22392

79. Funk WC, Blouin MS, Corn PS, Maxell BA, Pilliod DS, Amish S. et al. Population structure of Columbia spotted frogs (Rana luteiventris) is strongly affected by the landscape. Mol Ecol. 2005;14(2):483-96

80. Allendorf FW, Hohenlohe PA, Luikart G. Genomics and the future of conservation genetics. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(10):697-709

81. Smith AM, Green DM. Dispersal and the metapopulation paradigm in amphibian ecology and conservation: are all amphibian populations metapopulations? Ecography. 2005;28(1):110-28

82. Prachumwat A, Li WH. Gene number expansion and contraction in vertebrate genomes with respect to invertebrate genomes. Genome Res. 2008;18(2):221-32

83. Keilwagen J, Hartung F, Paulini M, Twardziok SO, Grau J. Combining RNA-seq data and homology-based gene prediction for plants, animals and fungi. BMC Bioinformatics. 2018;19(1):189

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: kgeissde; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3180-352X.

Corresponding author: kgeissde; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3180-352X.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact